Deployment Contracts

November 10 2015

I’ve been in a number of discussions recently around how to improve deployment workflows and how best to implement (and improve upon) 12-Factor applications in a continuous delivery environment. The following is a bunch of assumptions, desires, and implementations I have. It’s entirely aimed at what some organisations are calling their “platform team” and might not be applicable to all use-cases.

Helping everyone do more

For the majority of modern day platform teams their task is to understand the needs of the teams they support and to provide simpler processes for them to do what they need to do. Specifically:

- How can we help our colleagues go from nothing to something as quick as possible?

- How can we help our colleagues improve upon widely used services over time?

Implicit vs. Explicit

Many teams have to deal with a myriad of different requirements. Some even have fixed deadlines thrown in for extra measure. In those situations smart teams tend to start from a consistent mindset: they do less.

Even smarter teams standardise workflows to help the masses that depend on them go faster. Standardisation can take two routes: documentation and enforcement. Things you should do and things that you must do. Or, to put it another way, implicit vs. explicit.

In the rest of this post I’d like to discuss how you can make such tooling explicit to teams to help them go faster.

Brakes help you go faster

Product teams want to create and update applications, whenever they want, at speed.

To help them do this, you might build some tools to simplify the process. Along the way, you might also build some brakes in to help them go faster around the obstacles they’re likely to hit as they aim to get closer to production.

These tools might be libraries or services, but you’ll need a consistent artefact to ease communication. Let’s look at a small example of a UI and a machine-readable (JSON) file.

Starting a new application

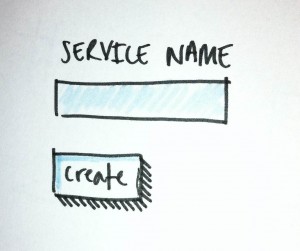

For any application to be worked on, it needs a name and a place to live. Let’s assume this interaction starts with a user interface:

When teams (or a product owner) submit a name for their new service a number of things happen automatically:

- a version control repository is created with the provided name

- a continuous integration job (for master and for any branches)

- a basic development environment for the application

- a status page showing the development state of the application (Is it running? How long ago it was both created and last modified? Who has worked on it?)

This means that a team can start prototyping and testing out ideas without having to worry about going beyond a basic development environment.

You might also abstract away a number of application decisions so that teams can concentrate on building their products. By providing libraries upfront, you can get get rid of a number of decisions for a team. Libraries that provide:

- a standardised way to do logging

- common endpoints for monitoring and healthchecks for web frameworks

- storage for short lived session data

- user authentication

Once a prototype has been built and briefly tested with users you might want to move it into increasingly more “real” test environments.

A machine-readable contract

It’s rare that applications run by themselves. In many cases they are one small part of a bigger system. However making sure all of these applications play nicely in a distributed system is no small feat.

To have an application be deployable in a number of different testing environments means providing some useful information for operators. In the following sections I’m going to describe a JSON file that might help ease moving a prototype into production.

Earlier in this post I showed a small sketch of a user interface. I described how it did a number of things automatically for a team. A fuller example could create a structured text file describing the application, a deployment contract. So what would this file look like?

{

"language": "clojure",

"script": ["lein test"],

"dependencies": [

{"service": "postgresql"},

{"service": "authentication"}

],

"healthcheck": "/healthcheck"

}

This JSON file would provide the deployment contract that an application makes with the environment that it’s going to run in. Moving up through various environments and into production would require more detail to be added to this file and for each environment to assert what’s required (exposed by the status page) before the team can continue.

To get into a similar pre-production environment the application’s manifest might have to provide a list of monitoring endpoints. This is useful because rather than monitoring endpoints existing in config management code it can registered (and updated) upon deploying a service into an environment.

The updated manifest file would look like this:

{

"language": "clojure",

"script": ["lein test"],

"dependencies": [

{"service": "postgresql"},

{"service": "authentication"}

],

"healthcheck": "/healthcheck",

"monitoring": [

{

"endpoint": "/user/*",

"percentiles": {

"90th": "X",

"95th": "Y",

"99th": "Z"

}

}

]

}

Getting to production

In terms of infrastructure environments, the final step associated with getting to production for some teams requires a security audit. The automatic registration of the manifest in an environment could manage this process when it’s triggered in one of the final pre-production environments.

The other step required to get into product is having a list of members of the team that are on-call for the application. The updated manifest would look like this:

{

"language": "clojure",

"script": ["lein test"],

"dependencies": [

{"service": "postgresql"},

{"service": "authentication"}

],

"healthcheck": "/healthcheck",

"monitoring": [

{

"endpoint": "/user/*",

"percentiles": {

"90th": "X",

"95th": "Y",

"99th": "Z"

}

}

],

"team": {

"oncall": [

{

"name": "Kushal Pisavadia",

"tel": "+447700000000"

}

]

}

}

With this in place a product team can happily choose to make a release of their application and put it into the production environment when they’re ready. A side benefit to operators is they now have a number of services that all describe how to test them, how to monitor them, how to escalate and what services depend on each other. That’s incredibly powerful.

In conclusion

Hopefully this description of a hand-held process from nothing to production is useful. It’s a small introduction to how platform teams might provide tools to help their teams move faster.

If you take anything away from this post it’s that we should start to think long term about the kinds of things that we as operators care about. Not containers or whatever new technology exists over the horizon, but how we help our colleagues deliver. Then when a new technology does arrive our only role will be to integrate it against our existing deployment contracts. In addition, by using such tools you can provide useful information to your infrastructure (about your services) to help you make better decisions along the way.

It’s worth saying that this shouldn’t be seen as a one size fits all solution. There are going to be many problems along the way and your job (as a platform/operations team) is to enable the teams that depend on you as much as possible. Sticking to a fixed script isn’t always the best move.

Extra reading: