Running a game day for GOV.UK

February 6 2015

This is a blog post I wrote for the GDS Technology blog. You can read the original here.

For much of January, GOV.UK had a firebreak. It’s where teams are given some time to investigate new ideas and clean up technical debt. As part of this we ran a game day. In this blog post I’m going to explain what game days are, what we did and what we learnt.

What is a game day?

The reality is that we can’t prevent the unexpected. However, there are some ways that we can prepare ourselves for it. We shouldn’t treat these unexpected events as outside the bounds of what we’re able to test. Instead, we should try to use them as a way to provide more feedback and help us become more resilient. The advantage of this is that it doesn’t rely on a big disaster to occur before we can learn how to improve our systems. The added benefit is that the scope can be defined by the team. This is where game days come in.

Game days are designed to let learning happen in a safe, controlled fashion. They’re exercises designed to teach teams how to adapt to the inevitable: system failure at all levels. Literature suggests that, in technical operations, they were created by Amazon in the early 2000s. They took the model of firefighter training — where major failures were injected into critical systems on purpose — and applied it to technology systems, software and the people surrounding them.

Things break, disasters happen and system failure is inevitable. The main thing about preparing for it is first to accept it. And we knew just where to start: the 2nd line team.

2nd line team

For those new to the term, the 2nd line team are the technical support team for GOV.UK. They’re the technical counterpart to the GOV.UK helpdesk, the 1st line team. They look at our monitoring systems and related metrics to make sure GOV.UK is working as expected, as well as doing some day-to-day gardening to make sure GOV.UK continues to operate in a healthy state.

The 2nd line team consists of three people, usually a web operations engineer and two software developers. They’re rotated on and off the 2nd line team on a weekly basis from the different product teams that work on GOV.UK. We’ve run a 2nd line team in some form since the launch of GOV.UK in October 2012.

For our first game day we were really interested to see how this team would cope with a number of disaster scenarios. This is because we’d expect them to be the first people looking into what was going on. All of the scenarios we ran were on our staging environment which is a one-to-one replica of our production environment (including traffic) so that we wouldn’t affect users of GOV.UK.

Structure of the game day

A number of us got together to discuss what we wanted to learn for our first game day. The common themes were about how prepared we were and how we could improve our systems.

Following on from this, four of us agreed to become the organisers for the first game day. We would be open to suggestions throughout the design process but would keep the details under wraps. We didn’t want to risk priming the 2nd line team. We used a number of brilliant resources that are available to help us design the game day. These range from a high-level overview through to a more hands on report.

One of our goals was to make sure the individuals on 2nd line didn’t feel they were the ones at fault. We wanted to make it very clear to them that being unable to find a fix for, or way around, the disaster wasn’t viewed as a failing on them as individuals or as a team. And should they need our help we’d more than happily jump in to “undo” what damage we’d caused. It was about learning where the gaps are in our systems to learn how to make them more resilient.

In the end we decided on two major scenarios: emergency publishing and complete data loss.

Emergency publishing

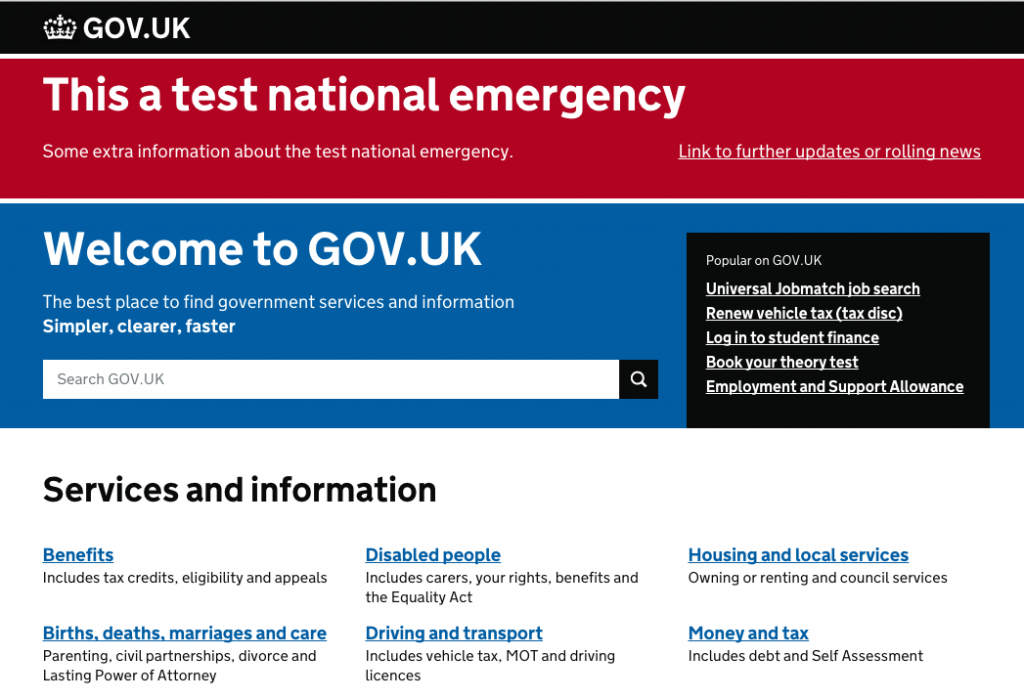

In the event of a national emergency it’s quite likely that the government will have an official response. They would publish a page of up-to-date information for members of the public. If this occurs, we show a clear banner on all relevant pages, linking through to a summary page with more relevant information.

We’ve run this scenario through a number of times, and automated a lot of it. For the game day we wanted to test how the 2nd line team would cope when the method of deployment and access to the environment where GOV.UK is hosted were both removed. They were asked at the start of the scenario to deploy the national emergency message. However, before they began we removed their access to the VPN and infrastructure that stores our documentation for such an event. The documentation itself uses static files and can be checked out as a local repository. As part of our 2nd line process members of the team are asked to keep an up-to-date local copy.

Some of the parts of the scenario are in our documentation, but we as the organisers weren’t sure whether the 2nd line team were aware of what to do in this situation. In the end, the 2nd line team found an alternate way into the environment which they all have relevant credentials for, deployed the national emergency message and completed the first game day scenario faster than we were expecting.

Complete data loss

For the second scenario of the day we asked the 2nd line team to go about their usual duties: to watch the monitoring tools and to pick stories from the 2nd line team’s backlog.

As this was going on, we began to remove entire databases from

GOV.UK. We ran the equivalent of DROP database; for each of the

database products we use and watched the aftermath. To make things

particularly difficult we also removed local backups that existed on

the database machines and separate backup machines that exist in the

virtual data center. This would force the team to use offsite backups,

which would be an unknown method for many of them as well as

significantly slower.

This is a terrible situation to experience for anyone, but we learnt a lot about gaps in our monitoring and documentation. There were a number of warnings across our infrastructure before critical alerts started to appear. It took the team a few minutes to realise what was happening, and to finally understand the repercussions.

Once the team realised what had happened, they quickly decided they needed to restore database backups and work out what else was going on. The team split into two groups: one set looking to restore database backups and the other investigating what was going on. They quickly saw that a member of the GOV.UK team (a game day organiser) had gone rogue and started causing damage. The 2nd line team removed credentials for the offending user and blocked their access.

When trying to restore database backups the team were having trouble following the documentation. The documentation for offsite backups was out of date because we had recently switched to a new offsite backup process. One member of the 2nd line team had worked on this recently, so they knew where to look and what to do. Had they not been on the team this could have been difficult to understand and they wouldn’t immediately know that they would need to speak to other members of the GOV.UK team.

As the 2nd line team started to restore database backups one by one they saw some oddness. One big thing we learnt from this process is that our offsite backups for PostgreSQL were truncated. They were backups from the PostgreSQL secondaries and had data missing. Overall the scenario was completed and database backups had been restored within a matter of hours.

What next?

After running game days for GOV.UK, we’ve realised what a rich source of feedback and insight we’ve been missing out on. They’ve shown that being able to simulate failure in a safe environment, where some of the stresses and pressures are removed is an incredible way to learn more about your systems.

The reality is that you get good at what you practice. If you can practice your responses to bad things happening, your reactions will hopefully be better when a real problem arises. With this knowledge, we’re going to run more game days and run them more often. Both across GOV.UK and within product teams.